December was an entomologically-challenging month with exceptionally wet and windy (but mild) weather which limited what I was able to achieve. Here are some points of note.

Chris Raper

I recently chanced across Chris Raper's website (http://chrisraper.org.uk/blog/) where he writes about his varied personal interests, but some of the content overlaps with his professional role at the Natural History Museum. I was particularly interested by his recent article on whether duplicates are a problem in biological recording. His answer is "it's not a problem at all – having more data is always better than less and duplicates are inherent to all biological data", but please read the article for yourself - http://chrisraper.org.uk/blog/biological-recording-dispelling-the-myths/

Also worth reading is his eloquet explanation of "Why we collect insects" - http://chrisraper.org.uk/blog/entomology/maintaining-an-insect-collection/

Common insects are suffering the biggest losses

My intention here is to try to focus on uplifting content, but some bad news is unavoidable. A recent research paper suggests that terrestrial insect decline is being driven by losses among more common species - the species with the most individuals (the highest abundance) are disproportionately decreasing in number. Examples include the Common Froghopoper, Philaenus spumarius. This counters the common narrative about biodiversity loss which focuses on declines of rare species: Disproportionate declines of formerly abundant species underlie insect loss. Nature, December 2023; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06861-4

Our rarest ladybird?

Trevor Pendleton's excellent YouTube channel continues to provide excellent entertainment and instruction. In a recent video he looked (unsuccessfully) for the Striped Ladybird, Myzia oblongoguttata: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTK58LC2Ky8

We only have four records for this species in VC55 - none since 2001. Although the recent weather has not been favourable, let's go and look for this arboreal species in the Scots Pines in 2024.

My Journal, December 2023

13.xii.2023 Another wet day, not as wet as some but a damp chill. Few birds in the garden but Stumpy the tail-less Dunnock haunts the ground feeder. Worked on spiders from Billa Barra in June.

14.xii.2023 A damp, chill day. Attempted to net winter Craneflies but failed so I ran the moth trap for 2 hours from dusk but caught nothing.

15.xii.2023 Finally visited Whetstone Cemetery, which was a bit underwhelming, but the adjacent St Peter's churchyard produced a good range of Arthropods from Ivy on mature trees.

16.xii.2023 Worked on the Whetstone samples from yesterday. In the afternoon finished stripping the Robinia trunk and placed it against the base of a fence for a new refugium.

18.xii.2023 Visited Leicester Forest East to check the palatial new LRES meeting venue. Online meeting with Paul Killip to discus Local Nature Recovery Strategy.

19.xii.2023 Worked on the Whetstone spiders from last week. Not many but they were my first fresh field sample for nearly a month (it's all been about processing the summer backlog recently).

20.xii.2023 Beat Ivy in Attenborough Arboretum. My first records for Derephysia foliacea and Buchananiella continua.

21xii.2023 Very windy.

22.xii.2023 Winter solstice. A wet one. Emailed out my entomological year in review/winter solstice review. It was still good to look back over what was not a massively memorable recording year but I feel guilty about committing a "round robin" crime. Most recipients seem to like it though. I'm still looking for the opportunity to commit to an entomological newsletter.

23.xii.2023 A short walk in Leicester Botanic Garden. Found a nearly skeletonised Muntjac but didn't investigate for carrion beetles as it was very smelly.

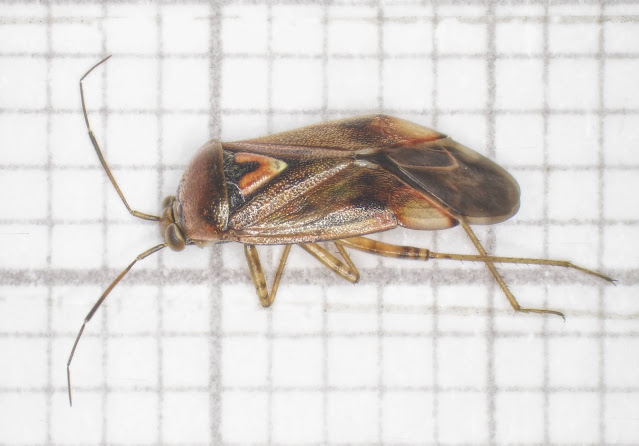

24.xii.2023 Reportedly the warmest Christmas Eve for 20 years, yet bringing in greenery from the garden for Christmas decoration only yielded two species this year, an Erigone and Rhopalus subrufus. In the evening, a green Lacewing appeared on the ceiling. What remarkable insects these are, so delicate in appearance and yet so robust.

26.xii.2023 A rare sunny morning so a walk at Launde. The fields are saturated with standing water in places I have never seen it before, and I have never seen the wood so wet.

27.xii.2023 Another named storm (Gerrit). Another very wet day.

30.xii.2023 Identified a few bugs sent to me before Christmas. First record of Leiobunum sp. A in VC55 - only a mile from my house. The arrival of this mysterious new species is a rather exciting end to the year: https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/leiobunum-sp-A